Notes on @mukhtara Yusuf’s Healing, Decolonising, Design

Mukhtara is beaming in from Tongvaland, now known to most as Pasadena California. Which parts are present in this talk? Ideally their plainest self: very inspired and very exhausted.

We could render exhaustion in ecological terms: more output relative to input. Healing might be understood as a rebalancing of that ratio. Many ecosystems are likewise exhausted. The taking of more than what is giving. What is required is healing the metabolic rift of the soul and the soil.

Indeed, our traumas get expressed and are interlinked with infrastructures of material distribution: of who gets what. Breakdown in electricity and roads, for instance, in places like Nigeria. You can’t help the feeling: what if this is intentional? Fracturing material networks is a way of fracturing the public and solidarity, maybe even the self.

First work shared: well, you’ve never seen a bright niqab around Ibadan, have you? Things are particularly dangerous at night if you’re dashing across the street in the dark. Thus: the Reflective Hijab. A clear functional/material intervention, but the other aspect is spiritual It is embroidered with a Quaranic verse for protection. It draws on the healing power that inheres in the actual act of touching, ingesting or otherwise physically interacting with the Word.

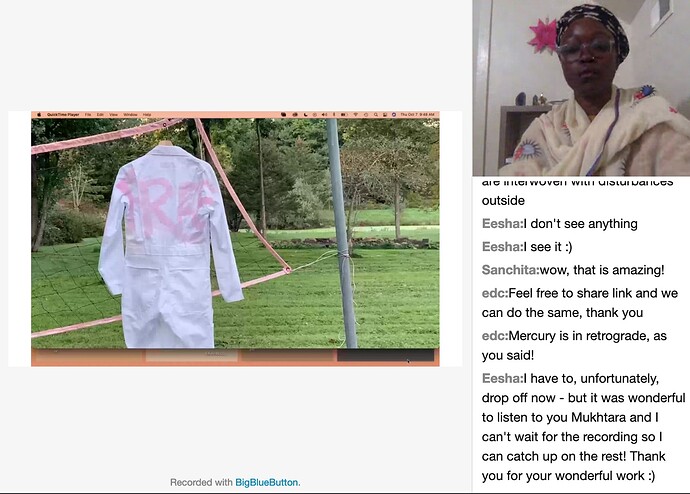

Second intervention:

A UV sensitive pigment applied to fabric is initially invisible, but appears when exposed to the sun. A commentary on incarceration in which the ability to feel the sun is controlled. Inspired by Nina Simone’s “Afro-pessimistic grief…of rehumanizing through the process of grieving freedom.”

Discussion:

@anand asks: is decolonizing design about giving up the sovereign privilege and autonomy of the designer? How, if so, does one design through the exhaustion? Well, Mukhtara says, it’s like how even though plants might be deprived of full sunlight they can still grow. So you must to some degree acceptance the difficulites for what they are and try and find what is possible within it. Designers in the Global South and in Nigeria in particular are wont to refuse conditions of infrastructural breakdown and marginalization, “the things that are made are what we think we are supposed to be making rather than what we can make with the resources available.” The design field perpetuates a kind of culture of perfectionism, premised on living in a rich country with continuously flowing resources. “My ancestors designed, they did architectural design, and no one drew anything. No external 2-D abstract representation. My ancestors designed functional objects…statuettes we used to commune with and used to worship, they didn’t need to be mass produced and they didn’t need electricity.”

If one valence of the possible is acceptance, maybe the other is insistent striving. Hence, @sanchita suggests, maybe to design is an act of hope, however slivered. Yes, Mukhtara agrees, and that hope might be a kind of fugitive, a core humanity that always remains free, that can never be fully captured by colonialism, by oppression. Even the premise of healing is a gesture of hope in that direction.